3 ways to improve genome catalogs

Metagenomics has revoluzionized microbiology. This sequencing technology enables researchers to gain insight into the composition and functional potential of a microbial community in situ. Even though it is called metagenomics, the sequenced reads were not analyzed on a genome level due to technical limitations, especially the lack of reference genomes for many microbiomes.

In 2017, Parks et al. published nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), which substantially expanded the tree of life (Parks et al. 2017). Since then, we have entered an era of large-scale (re-)assembly in metagenomics. Many researchers started to assemble MAGs from various metagenomes, often recovering dozens of new species. 2017 also marks the year of the beginning of my PhD. So I had the opportunity to do my PhD during this exciting time. I worked mainly on a pipline that allows producing such MAG catalogs with only three commands. We applied our pipeline to all the samples from the mouse genome in order to recover a comprehensive catalog of genomes for this microbiome.

With this study now published, I reflect on what can be improved for the benefit of others that take the challenge to create comprehensive catalogs for their microbiome of interest.

1. Use co-binning

Most studies use single-sample assembly and binning because it allows the processing of each sample in parallel, making the approach very scalable. The downside of this approach is that the coverage information from only one sample is used. But using the differenctial coverage from multiple samples can be very useful for binning. There are alternatives, co-assembly, and cross-mapping, which allow for the use of differential abundance, but they have their problems and challenges 1.

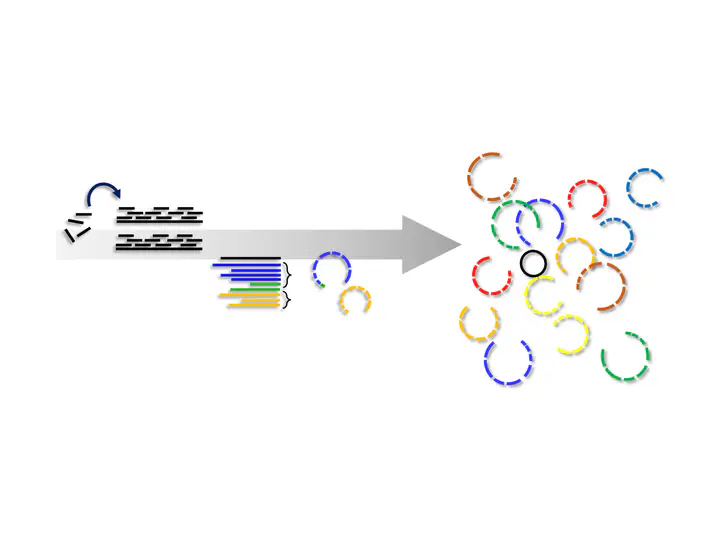

Recently, a new strategy for binning was developed, which I call Co-Binning2. The method works as follows:

- Assemble each sample separately

- Concatenate the assembly of all samples to one

- Map the reads from all samples to the concatenated assembly

- Bin the contigs from each sample separately, but use the differential abundance from all samples.

This strategy more or less combines the advantages of the other binning strategy. It doesn’t require co-assembly and allows for the use of differential abundance and scales to many samples (~100). This strategy is implemented in the two tools Vamb and SemiBin. The authors of Vamb also claim that it can disentangle genomes from different subspecies up to 97% ANI, which I find pretty interesting. SemiBin uses not only the abundance but also the taxonomic annotation. Both binners could, in theory, also be used for Eukaryote binning. The only adaptation to SemiBin would be to use a taxonomic annotation that includes Eukaryotes.

So, If you plan to recover many genomes from metagenomes, think about trying out these new binners. I already implemented both binners in metagenome-atlas.

2. Optimize quality estimation

The second step comes after realizing that the MAGs are not as good as we think – even the ‘high-quality’. The part has to do with the fact that MAGs are just of lousy quality due to limitations of the computational pipelines. Manual curation is needed (Chen et al. 2020). But part has to do with the quality estimators telling us they are of good quality when reality, they are not.

Use up-to-date databases for genome evaluation

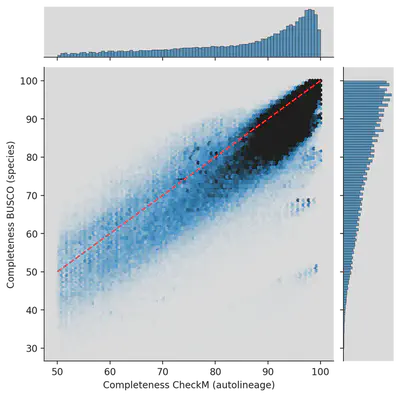

The whole field uses checkM, which is an elegant tool. However, its database was not updated since 2015! Everybody is waiting for version 2 of the tool, but in the meantime, one can use BUSCO which works similarly, is based on the up-to-date OrthoDB markers, and works for eukaryotes.

Don’t automatically select marker-gene

CheckM and BUSCO automatically select the most appropriate marker gene set for evaluation, which is very handy, but it might also bias the results. For example, a genome is incomplete. Its taxonomic lineage cannot be determined, which causes it to be evaluated at the most basic level. If by chance, it contains many of the basic marker genes, which often cluster together in operons, it’s estimated as highly complete.

If the genome in question is from a completely new species, there is no way to circumvent this, and it’s good that the more unknown genomes are evaluated at more basic levels. However, if the genome belongs to an abundant species, you likely have hundreds of other genomes from the same species (in a radius of 95% ANI). In the worst case, a bad genome evaluated at the most basic level could be estimated to have better quality than other genomes evaluated with the more extended marker gene sets.

If you have multiple genomes of the same species, which you have if you create a genome collection, you want them to be all evaluated with the same marker gene set. Together with Matija Trikovic, we made a snakemake pipeline that does exactly this.

We re-analyzed genomes from the UHGG and HumGut databases with BUSCO and the same set for each genome. What was estimated by CheckM to be 99% complete came out to less than 50% for some genomes! Which is due to both effects. 1. BUSCO has a more up-to-date database, and 2. We evaluated genomes from the same species cluster not automatically but with the same marker genes as the representative.

Ad-hoc quality estimation

This point is more an idea than concrete advice. If you have many genomes from the same species (or higher taxonomic clade) from a specific environment, then per definition, you would have the best collection of genomes to evaluate the completeness. You could define an ad-hoc set of marker genes, e.g., genes at 95% identity present in >90% of the genomes. Then you turn it around and ask how many genomes have >90% of these genes. It helps to refine completeness for a given species.

2. Filter chimeric genomes

The ad-hoc quality estimation doesn’t help with contamination. But recently, new tools came out that check if genomes are chimeric — for example, GUNC or Charcoal. Taxonomically annotating contigs allows identifying contigs with incongruent taxonomy, aka chimera. This strategy is reference-based, but it provides filtering with a much broader scope than only looking at the marker genes.

Finally, with more and more genome catalogs out there, I think the question becomes more crucial about efficiently using them. We choose 1 genome per species as a reference, which we use to map reads against it or build a Kraken DB. This approach glosses over much of the strain variation already contained in the genome collections. In some publications, the authors make Kraken DBS with many genomes per species, which increases the mapping rate overall, but when estimated on the species level, it’s lower (Nasko et al. 2018).

I could write more, but I leave it there for my first blog on metagenomics. Please reply to the Tweet below or mail me if you have comments and discussions.

My first blog post about ways to improve current genomes catalogs for metagenomics https://t.co/bBtM2DbUms

— Dr. Silas Kieser (@SilasKieser) April 12, 2022